Anyone who charts the development of thrillers throughout the history of American movies must reserve a place of honor for John Frankenheimer’s The Manchurian Candidate, the not-so-missing link between grimly paranoid, seriously noirish melodramas of the Cold War-fixated ’50s, and darkly ironic, brazenly fantastical superspy escapades of the swinging ’60s. You can savor the transition for yourself when Turner Classic Movies cablecasts this classic Tuesday evening.

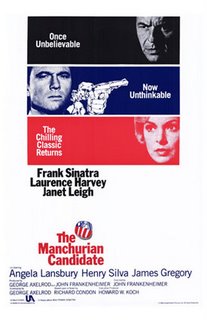

Anyone who charts the development of thrillers throughout the history of American movies must reserve a place of honor for John Frankenheimer’s The Manchurian Candidate, the not-so-missing link between grimly paranoid, seriously noirish melodramas of the Cold War-fixated ’50s, and darkly ironic, brazenly fantastical superspy escapades of the swinging ’60s. You can savor the transition for yourself when Turner Classic Movies cablecasts this classic Tuesday evening.Frankenheimer’s impressively stylish and audaciously stylized tale of brainwashed assassins, duplicitous politicians and international conspiracies is at once unmistakably of its time and undeniably timeless. There’s something uniquely appropriate about its timing as well. Consider this: Manchurian Candidate had its New York premiere on October 24, 1962 – two days into the Cuban Missile Crisis, a real-life doomsday scenario that could have triggered World War III, and eight months before the U.S. release of Dr. No, the very first larger-than-life, licensed-to-thrill movie featuring the shaken-not-stirred James Bond.

But wait, there’s more: The 007 film was based on a book famously enjoyed by President John F. Kennedy, commander in chief during the ’62 contretemps over nuclear warheads in Cuba. President Kennedy also had words of praise for The Manchurian Candidate, Richard Condon’s original 1959 novel (which scripter George Axelrod ingeniously adapted for the screen), and Kennedy's approval reportedly did much to allay any apprehensions about filming a book that involved the potential termination of a presidential hopeful.

(According to Hollywood legend, Frank Sinatra, star and co-producer of Manchurian Candidate, curtailed all distribution of the movie after JFK, a close friend, was assassinated. The truth is far more prosaic: Sinatra withheld the movie from re-release until 1988 because of a squabble over profits.)

Very much like Stanley Kubrick’s equally disconcerting Dr. Strangelove, Or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb (which arrived in theaters just 15 months later), Frankenheimer’s classic initially upset many moviegoers – and confounded a few clueless critics – by exploiting and satirizing the free-floating, wide-ranging paranoia of its Cold War era. Indeed, Manchurian Candidate struck many tender-hearted souls as by far the more irresponsible of the two films, simply because it isn’t so obviously a black comedy.

Combining elaborate showmanship with an urgent sense of purpose, it appears at first glance to be a conventionally dead-serious thriller, shot in aptly somber black and white – especially effective during faux newscasts, Senate hearings and political convention coverage – and edited with a virtuoso skill that, back in the 1960s, greatly impressed a wanna-be moviemaker named Steven Spielberg. (“When I saw The Manchurian Candidate,” Spielberg recalled in a 1977 interview, “I realized for the first time what film editing was all about.") Only gradually does the movie reveal its true colors as over-the-top, larger-than-life pulp fiction fueled with impudence, iconoclasm and aggressively impolite wit.

The prologue, set during the Korean War, establishes Sgt. Raymond Shaw (Laurence Harvey) as a humorless prig who’s intensely disliked by his men even before he leads them into an ambush during a late-night patrol. After the opening credits, however, Shaw returns home as a celebrated hero – and Medal of Honor recipient – for rescuing his unit from behind enemy lines. Whenever he’s asked about his former comrade-in-arms, Capt. Bennett Marco (Frank Sinatra) automatically replies: “Raymond Shaw is the kindest, bravest, warmest, most wonderful human being I’ve ever known in my life.” Marco knows, with absolute certainly, that the testimonial is a lie. But that doesn’t keep him from reflexively repeating it at every provocation.

Frankenheimer teases us by slowly, suspensefully revealing the truth in literally nightmarish flashbacks. It turns out that Shaw, Marco and their men were brainwashed while imprisoned in Manchuria, then placed on display before an audience of Soviet, Chinese and North Korean operatives. To prove the effectiveness of their “Pavlovian technique,” spylord Yen Lo (Khigh Dhiegh) ordered Shaw to kill – on stage – two soldiers under his command. Unfortunately, the demonstration was a success. Even more unfortunately, Shaw was implanted with post-hypnotic suggestions, enabling deep-cover agents to use the “war hero” as an unwitting assassin. The other surviving captives? They were implanted with the “kindest, bravest, warmest” bunk, all the better to make the fraud plausible.

While Marco tries to convince his skeptical superiors that his repressed memories aren’t deranged fantasies, Shaw sets his sights on a journalistic career while avoiding all unnecessary contact with his smothering mother (Angela Lansbury), a honey-voiced, steel-willed harridan who’s grooming her current husband, Sen. John Iselin (James Gregory), for a White House bid. Shaw frankly despises his buffoonish stepfather, and with good reason: The senator is an opportunistic rant-and-raver who claims to have a list of Communist agents at work in the State Department (just like the real-life Sen. Joe McCarthy, whose Red-baiting witch hunts were still fresh in the minds of moviegoers in 1962). In truth, Sen. Iselin’s charges are inventions, impure and simple, concocted by Mrs. Iselin. And, mind you, that’s not the worst trick up her sleeve.

Manchurian Candidate is an equal-opportunity offender: It takes so many potshots at Left and Right targets that it was condemned as anti-American and crypto-fascist at the time of its release. Iconographic symbols of America – most often, images of Abraham Lincoln – are repeatedly used for satirical intent, to emphasize how patriotism can be the first refuge of politically-savvy scoundrels. (The movie often recalls, and at one point paraphrases, a complaint occasionally aired during the ’50s: “Joe McCarthy couldn’t do more damage to this country if he were a paid Soviet agent!”) And yet, at the same time, Frankenheimer also indicates that paranoia sometimes is a perfectly rational response to worst-case scenarios. His movie cuts both ways, and it cuts very deep.

(It also coined a phrase that remains, more than four decades later, irreplaceably useful as shorthand in our pop-culture slanguage. Just a few months back, conservative columnist David Brooks despaired over the bumbling of George Bush during a Meet the Press confab: “[S]ometimes in my dark moments, I think he's The Manchurian Candidate, designed to discredit all the ideas I believe in.”)

It would have been asking too much, I suppose, for Jonathan Demme’s updated remake of The Manchurian Candidate (which pops up on various Showtime channels throughout August) to have the same stunning impact as Frankenheimer’s masterwork. But I don’t think it’s out of line to complain that the 2004 misfire wasn’t sufficiently sneaky and distressing on its own terms. Far too much of the Demme’s Candidate came across as obvious and literal-minded, if not leaden and ham-handed. And it didn’t help that Demme gave away too much, too early, while unwinding his recycled plot.

In the remake, which Demme directed from a script by Daniel Pyle and Dean Georgaris, the Soviet and Chinese operatives were replaced by agents of a Halliburton-type conglomerate. But instead of brainwashing U.S. soldiers during the first Gulf War, the bad guys implanted will-snapping computer chips in the brains of their captives. And instead of killing anyone who got in the way of his stepfather’s ascent, the new Raymond Shaw (Liev Schreiber) was himself a candidate for national office – a candidate, of course, who would be controlled by his corporate masters. (All of which raised some indelicate questions: Why did the bad guys go to so much trouble? Instead of brainwashing a candidate, why didn’t they just make really big donations to his campaign fund?)

To be fair: Denzel Washington was terrifically compelling as the new Ben Marco, a man desperate to uncover the truth while maintaining a tenuous grip on his sanity. And Meryl Streep was good enough as Eleanor Shaw, Raymond’s controlling mother, to occasionally make you forget how brilliantly Lansbury played the same part in the 1962 version. Overall, however, Demme’s The Manchurian Candidate was nothing more than a fitfully exciting trifle that was reasonably involving and quickly forgotten. In the history of American movies, it likely will be remembered, if at all, only as a footnote.

3 comments:

I thought it a little strange that you took care to mention the writers of the one film you didn't care for but let George Axelrod and Terry Southern remain anonymous. So often, screenwriters take the blame when a film fails, and go unnoticed when everything works. Ernest Lehmann wrote an essay called 'Writing Directors' Touches' and that's precisely what he did for Alfred Hitchcock.

If any two movies belong to the screenwriter, it's The Manchurian Candidate and Dr. Strangelove. At no no other moment in their careers did those notably humorless auteurs, Frankenheimer and Kubrick, show anything like the brilliant, biting satiric wit of these two films.

Steve:

You are not only right, you are damn right. The oversight was unforgivable. And, hey, since it's my blog, I'll go back and correct it. Many thanks. Seriously.

JL

I am perfectly happy to see George Axelrod and Terry Southern get well-deserved credit but having had dinner with Southern once, where Dr. Strangelove was a major topic of his reminiscences, I feel certain he would have been the first to protest the idea that Strangelove belonged to the screenwriter --or that Kubrick was notably humorless and never showed biting satiric wit on any other occasion. (True, no other movie of his is as outright comedic, but there's obviously the same sensibility toward the military at play in both 2001 and Full Metal Jacket, for starters.)

Kubrick began the adaptation of Peter George's novel with George, but eventually came to the conclusion-- and I suspect The Manchurian Candidate may have influenced him in this-- that something as horrific as nuclear war could only be dealt with satirically. That was when he engaged Southern, and (per Southern) the two of them recast George's plot in black comic terms. Kubrick has a screenwriting credit along with George and Southern, and Southern is only one of many Kubrick screenwriters who made it clear that he was not only a co-writer but the most stimulating, if frustrating and demanding, collaborator they ever had.

Post a Comment